(OG 910)

Track listing: Nicrotto/Seven For Lee/Sweet F.A./Three For All

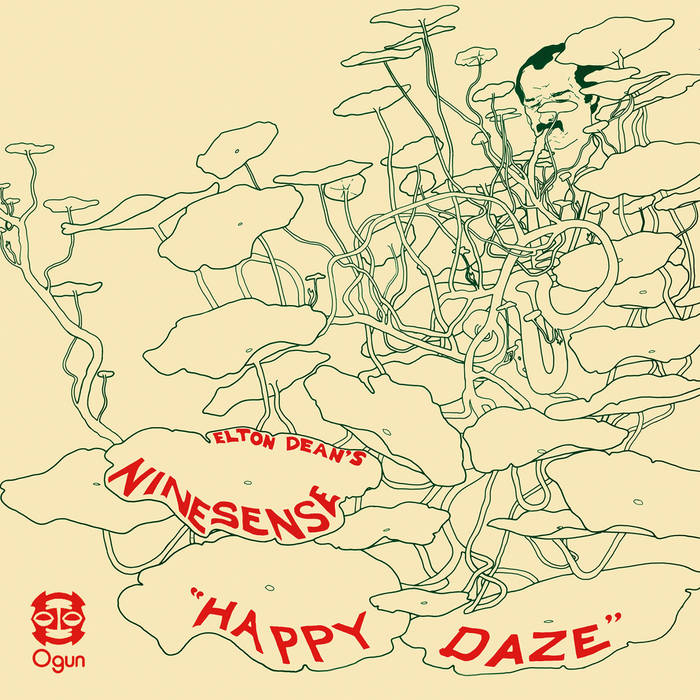

Elton Dean (alto sax and saxello), Alan Skidmore (tenor sax), Harry Beckett (trumpet and flügelhorn), Marc (sic) Charig (cornet and tenor horn), Nick Evans, Radu Malfatti (trombones), Keith Tippett (piano), Harry Miller (bass), Louis Moholo-Moholo (drums). Recorded at Redan Recorders, Queensway, London W2 on 26 July 1977. Released: November 1977. Produced by Elton Dean and Keith Beal. Photography: “Yuka.” Sleeve design: uncredited.

If you wondered why so much of recorded British modern jazz of the seventies is comprised of stolid, stodgy “suites,” then blame the Arts Council. As much of a box-ticking enterprise then as it is in these starved Let’s Create days today, they were never going to give Hard Working Taxpayers’ Money to jazz groups just to tour or record willy-nilly and be themselves. Oh no, the musicians had to prove they were “serious” by which it was meant they should come up with classical music compositions or, indeed, “suites.”

Most British jazz musicians of the period, needing to eat, regarded the matter as an occupational hazard necessary to negotiate in order to get that Government grant, and most worked their way around the system. Happy Daze was commissioned by and for the 1977 Bracknell Jazz Festival, yet three of its “movements” were recycled Ninesense band book stalwarts. On the invaluable Live At The BBC compilation of sessions released by the Hux label in 2004 – not easy to find today, but worth picking up if you see it at a reasonable price – one is reminded that “Nicrotto,” “Seven For Lee” and “Sweet F.A.” were once called “Nicra,” “Seven For Me” and “Sweet Francesca” respectively (meanwhile, the same collection’s “Bidet Bebop” would later crop up on OG 410 as “Dede-Bup-Bup”).

Therefore, faced with a commission and money, Dean yanked these tunes together with a fourth and welded them to a vague concept – thus a “suite.” It was recorded on the Tuesday after the band had performed it at Bracknell. And although annotator Steve Lake does his sprightliest to get us interested, Happy Daze has some flaws which I think are now endemic to the condition of British modern jazz of the mid-to-late seventies.

It begins well enough with swirling piano and drums, and echoing brass fanfares, like a huge ship getting ready to set sail from port, Harry Miller furiously sawing away with his bow as though cleaning the timbers. Then all calms down and the ship is at (a fairly placid) sea (the drift of virtual cumulonimbi seems to have a lot more in common with Keith Tippett’s approach to composition) – but the waves soon turn choppy, and the premature trombone iceberg of Nick Evans and Radu Malfatti looms up in the near distance.

With the presence of both trombonists, and Keith Tippett, the aim seems to have been to recreate the intensity of Listen/Hear, with the long and vaguely sinister modal build-up mutating into rapid-fire free play. Indeed, given that this piece was already familiar to Ninesense under the title of “Nicra,” it’s possible that it could have been a starting point for what happens on OG 010.

Only this time it doesn’t catch fire. It’s actually a bit of a damp squib. The two ‘bonemen blow rather desultorily around each other and even Tippett can’t really get the sparks to ignite. I suspect one of the main reasons why Listen/Hear was such a spectacular success was that these three men were faced with an unfamiliar rhythm section, which provoked them to try different improvisational tactics. With Miller and Moholo-Moholo they sound, ironically, just too comfortable and it becomes free jazz by rote.

Furthermore, “Nicrotto” is yet more evidence for the prosecuting counsel seeking to address the question of what went wrong with British (or British-based; four of Ninesense’s members did not come from the U.K.) free-to-modern jazz from around 1977. Paramount in finding an answer is the seeming incapability of musicians to differentiate between improvising, live, and making records, which like it or not are entities of structure whose purpose is to be listened to repeatedly.

As well as placing a barrier between the music and any potential listeners. “Nicrotto” is an illustration of one thing British contemporary jazz on record got continually wrong, namely the “PUTTING THE DIFFICULT BIT FIRST” malady. Beginning your album with its longest (twelve minutes) and most extreme and uncompromising (or, in my perverse view, its most conservative) track is asking an awful lot of your listeners. It’s like erecting an electrified barbed wire fence designed to keep trespassers out. As well as any curious passers-by who might want to check your music out but, repelled by what they initially hear, quickly slink away. And to me it’s as sheerly predictable in its way as anything Kenny Ball might have played on television at the time.

Things, happily, do improve – to a point. “Seven For Lee” is a great, snappy jazz-rock modal workout with a solid underlying core of rhythm. A bit third/fourth-album Soft Machine, a lot more second-album Keith Tippett. It lacks the maniacal nature of the BBC Jazz In Britain reading, which features Tippett, on celeste of all instruments, going frankly insane with his no-tone clusters, but Dean, in a yearning-verging-on-panicking John Surman mood, does very well on saxello as Tippett carefully swings his accompanist’s pendulum from straight comping to free-ish upper register rabbit runs and back. Mark Charig, making his third (and possibly misspelt?) consecutive Ogun appearance, not so much. His solo is fine in itself, moving from Henry Lowther-esque tarnished elegance to Don Cherry-style questing, whinnying upper register whimpers – but seems superimposed on the music, rather than naturally arising within it. And whatever his many virtues, this piece requires rhythmic acumen, and while I don’t expect fluid bebop runs or indeed any bebop runs at all, the sad fact is that Charig just doesn’t swing.

“Sweet F.A.” is an Ellingtonian ballad, or an element of a ballad anyway – these pieces are basically one sequence repeated ad infinitum – which inspires a strong and generally lyrical tenor solo from Alan Skidmore that only really goes off the mark (though never over the edge) when somebody presses the “now play free” button (more about that in a moment). Tippett, however, gives us the album’s finest solo here, and probably one of his greatest recorded solos, swimming between limpidly forlorn whole-tone chords and Bill Evans-via-McCoy Tyner lyricism – it’s as if he is examining, then exploring and extending, the implications of the bitonal phases of Evans’ “Peace Piece.” Then he switches to a long, angry fast run which he takes to the point of detonation before electing to settle back, meditatively and musically. If you don’t buy the album for any other reason, get it to hear this.

The record concludes with the bright waltz of “Three For All,” an attractive fragment almost worthy of Kenny Wheeler’s big band – you can imagine Norma Winstone’s voice singing in unison with the horns. The first featured soloist is Dean again, this time on alto, and the proceedings bounce along relatively amiably until…

Well, it seems like a conditioned response, but it keeps happening on Ogun records of this middle period. The moment where an inaudible switch is pressed and suddenly horn and piano go off-piste and into the world of free improvisation. Therefore Dean is quite lyrical until Tippett begins scuttling across the keyboard like an impatient haven’t-had-anything-since-breakfast mouse, whereupon we get the howls, the whines, the noises. Dudu Pukwana and a disciplined Mike Osborne could have pulled this type of caper off, but once more to Joe “What Is Jazz In 1977?” First-Time Listener it’s the equivalent of a barking Alsatian warning strangers away, and poor Joe ends up running a long way away from this field of music altogether. Huh? Why can’t they play straight? They were doing so well…are they trying to prove a point? Then good old Harry Beckett arrives to calm things down and get them back on course, although even he gets momentarily diverted into mock-freeisms (one very major problem with Happy Daze is that its solos are, for the most part, far too long – perhaps to compensate for this “suite” only having four components?). Finally there’s another theme statement which erupts quite unnecessarily into a mass freeform shriek (or, in this case, more like murmurs of complaint) before concluding with Tippett’s booming bottom notes to mark the ship having irretrievably sunken.

My problem with records like this is that their “free” components are not really free at all and are, if anything, inimical to those unaware of the workings of the British free jazz/improv labyrinth. And focusing on the “out-there” stuff just isn’t what Ogun is good at. The freakout bits are stimulating in moderation or totality. But some of these musicians seem to me to do “free” so badly. They’re so much more convincing when they utilise free playing as a natural corollary in the context of their music, or rather a lot of time when they simply…play jazz.

When people fondly recall Ogun Records they think of Spirits Rejoice!, Family Affair, S.O.S., Tandem, Frames, Blue Notes For Mongezi, Procession. Ingeniously-constructed albums full of genuine inventiveness coexisting with the rawest of emotions. Catchy tunes and danceable rhythms launched into space. Or they think of Ovary Lodge, Voice, Listen/Hear, Pipedream, The Cheque Is In The Mail, The Longest Night – an incredibly diverse range of approaches to group improvisation which always give off the scent of the new and unexpected.

But these are all records of adventure. Discordancy and “weirdness” for their own sakes cannot go anywhere. Instead they just pile up and gather dust. It’s a bit like the cumulatively tiresome parade of gore and grotesquerie we were fed on Inside No 9. It isn’t the sub-Tobe Hooper horror tropes or the ceaseless fourth-walling that we remember from that series. It’s “The 12 Days Of Christine.” Or “Bernie Clifton’s Dressing Room.” Or “Love’s Great Adventure.” Or even “The Referee’s A W***er.” Well-constructed stories containing both emotion and heart.

Ninesense’s reputation, in any case, is mainly based on their live work. Neither of their two Ogun albums really captured the spirit of the band and I don’t suppose, by definition, any recording could have done. You had to be there (and even then – I saw them at Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre in March 1980. From memory I think it was Larry Stabbins and Marcio Mattos in the band rather than Skidmore and Miller. Use the comments box below to put me right if necessary). I have kept Happy Daze because it does show endeavour and, in one instance, potential greatness. And the tunes (or the three tracks which have palpable tunes) are very good. My central problem with the record is that its endeavour is misapplied. It needed to have come in a little, having been “out there” for so long and so resolutely.

Current availability: Reissued, in tandem with most of OG 900, on CD in 2009, and made available on download in February 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment